Learning from US Mortalities in 2020

“When you repeat a mistake, it is no longer a mistake: it is a decision.”

– Paulo Coelho

Much has been written in the last few months about the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) findings that life expectancy declined in the United States by a full year during the first six months of 2020. This startling number is in line with previously published findings indicating that US life expectancy would decline by 1.1 years as a result of the current pandemic, with racial and ethnic minorities facing the most severe impacts.

In our roles as healthcare providers, there is a lot to consider in these data. The findings represent a single-year decline unlike any seen since World War II in the 1940s. It is a step backward of almost 20 years in terms of public health efforts to close the life expectancy gaps that exist among US minority and socially vulnerable populations.

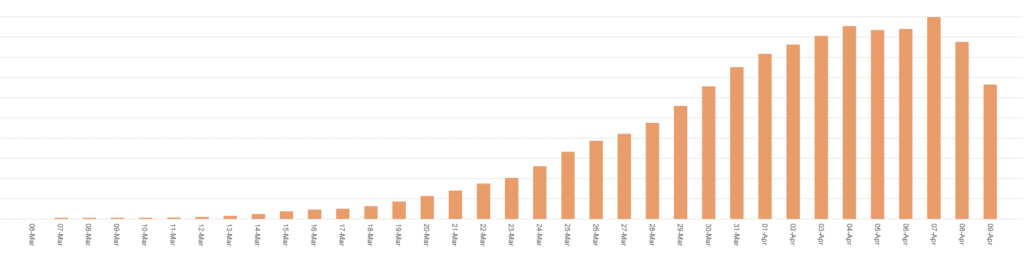

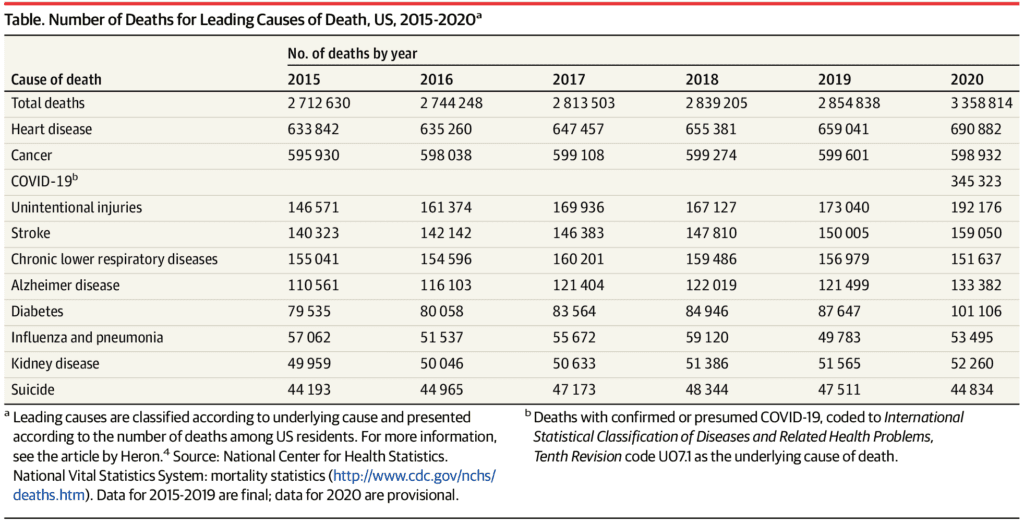

A recent publication in JAMA provides an expanded view of the challenges brought on by the pandemic as seen in the disheartening mortality numbers from 2020 (see table below). While the leading causes of death are similar to prior years, there are significant spikes to consider as we try to learn from what we have experienced in the last year. These spikes can point toward areas where immediate intervention could be the difference between 2020 data and what 2021 data may look like.

As anticipated, mortality associated with COVID-19 constituted the lionshare of the overall increase. Alarmingly, several causes of death (compared to 2019 numbers) were associated with substantially higher numbers, including those from heart disease (4.8%), Alzheimer disease (9.8%), and diabetes (15.4%).

And while cancer-related deaths were unchanged in the 2020 data, there was a significant impact on this population as well and a measurable adverse impact on mortality may well manifest itself in coming months and years. Already in 2021, radiation oncologists report that patients are consistently arriving for care with more advanced stages of cancer than in pre-pandemic times, one sign that an impact of treatment interruptions may still be felt.

But there is an opportunity for us to ensure that these 2020 figures do not become a new trend. Rapid increases in deaths or identification of late-stage diseases are in many cases attributable to decisions made by patients to avoid or delay care until the situation has become dire. As regular check ups were skipped and signs of worsening symptoms not shared with caregivers, opportunities for healthcare providers to intervene were less available.

It might be tempting to think that as COVID-19 vaccinations increase and infections decrease, patients will be willing to return to hospitals and provider offices as before. But that return won’t begin to close the health gap for Black, Latino and other minorities and socially vulnerable populations who, these data clearly tell us, have disproportionately borne the mortality, economic, and psychological brunt of the pandemic. We must change practice to change minds and to meet patients’ changing expectations of:

- More community: Work with local groups to identify and address barriers to basic health care, not to mention the barriers to dental care, housing, healthy food, green spaces, and so on

- More trust: Highlight the voices of minority medical professionals who can help patients build confidence in the care decisions they are making (as this Cincinnati group did)

- More convenience: Create opportunities for care to fit into a patient’s geography and schedule with less time required physically in the hospital or physician office

- More clarity: Improve communication and provide physicians with the data needed to diagnose patients accurately and determine effective treatment plans with patients as partners

Leading healthcare providers are adapting. From fast and efficient telehealth consultations to improved cardiac testing with coronary CT in both acute and outpatient settings, options are improving to deliver treatment with an increased understanding of each patient’s individual situation.

But if these innovations improve care only for those who are already getting care, then these dismaying 2020 mortality data will be our new normal. The adage that “all healthcare is local” reminds us that we can make a difference where we are now. As we learn from the past 12 months and reach out, we can arrive at a better place than where we began the journey.

And that will be a very conscious decision.

— A perspective from HeartFlow Chief Medical Officer, Campbell Rogers, MD

Bio | LinkedIn